Chapter 14: The Milky Way

Chapter 1

How Science Works

- The Scientific Method

- Evidence

- Measurements

- Units and the Metric System

- Measurement Errors

- Estimation

- Dimensions

- Mass, Length, and Time

- Observations and Uncertainty

- Precision and Significant Figures

- Errors and Statistics

- Scientific Notation

- Ways of Representing Data

- Logic

- Mathematics

- Geometry

- Algebra

- Logarithms

- Testing a Hypothesis

- Case Study of Life on Mars

- Theories

- Systems of Knowledge

- The Culture of Science

- Computer Simulations

- Modern Scientific Research

- The Scope of Astronomy

- Astronomy as a Science

- A Scale Model of Space

- A Scale Model of Time

- Questions

Chapter 2

Early Astronomy

- The Night Sky

- Motions in the Sky

- Navigation

- Constellations and Seasons

- Cause of the Seasons

- The Magnitude System

- Angular Size and Linear Size

- Phases of the Moon

- Eclipses

- Auroras

- Dividing Time

- Solar and Lunar Calendars

- History of Astronomy

- Stonehenge

- Ancient Observatories

- Counting and Measurement

- Astrology

- Greek Astronomy

- Aristotle and Geocentric Cosmology

- Aristarchus and Heliocentric Cosmology

- The Dark Ages

- Arab Astronomy

- Indian Astronomy

- Chinese Astronomy

- Mayan Astronomy

- Questions

Chapter 3

The Copernican Revolution

- Ptolemy and the Geocentric Model

- The Renaissance

- Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model

- Tycho Brahe

- Johannes Kepler

- Elliptical Orbits

- Kepler's Laws

- Galileo Galilei

- The Trial of Galileo

- Isaac Newton

- Newton's Law of Gravity

- The Plurality of Worlds

- The Birth of Modern Science

- Layout of the Solar System

- Scale of the Solar System

- The Idea of Space Exploration

- Orbits

- History of Space Exploration

- Moon Landings

- International Space Station

- Manned versus Robotic Missions

- Commercial Space Flight

- Future of Space Exploration

- Living in Space

- Moon, Mars, and Beyond

- Societies in Space

- Questions

Chapter 4

Matter and Energy in the Universe

- Matter and Energy

- Rutherford and Atomic Structure

- Early Greek Physics

- Dalton and Atoms

- The Periodic Table

- Structure of the Atom

- Energy

- Heat and Temperature

- Potential and Kinetic Energy

- Conservation of Energy

- Velocity of Gas Particles

- States of Matter

- Thermodynamics

- Entropy

- Laws of Thermodynamics

- Heat Transfer

- Thermal Radiation

- Wien's Law

- Radiation from Planets and Stars

- Internal Heat in Planets and Stars

- Periodic Processes

- Random Processes

- Questions

Chapter 5

The Earth-Moon System

- Earth and Moon

- Early Estimates of Earth's Age

- How the Earth Cooled

- Ages Using Radioactivity

- Radioactive Half-Life

- Ages of the Earth and Moon

- Geological Activity

- Internal Structure of the Earth and Moon

- Basic Rock Types

- Layers of the Earth and Moon

- Origin of Water on Earth

- The Evolving Earth

- Plate Tectonics

- Volcanoes

- Geological Processes

- Impact Craters

- The Geological Timescale

- Mass Extinctions

- Evolution and the Cosmic Environment

- Earth's Atmosphere and Oceans

- Weather Circulation

- Environmental Change on Earth

- The Earth-Moon System

- Geological History of the Moon

- Tidal Forces

- Effects of Tidal Forces

- Historical Studies of the Moon

- Lunar Surface

- Ice on the Moon

- Origin of the Moon

- Humans on the Moon

- Questions

Chapter 6

The Terrestrial Planets

- Studying Other Planets

- The Planets

- The Terrestrial Planets

- Mercury

- Mercury's Orbit

- Mercury's Surface

- Venus

- Volcanism on Venus

- Venus and the Greenhouse Effect

- Tectonics on Venus

- Exploring Venus

- Mars in Myth and Legend

- Early Studies of Mars

- Mars Close-Up

- Modern Views of Mars

- Missions to Mars

- Geology of Mars

- Water on Mars

- Polar Caps of Mars

- Climate Change on Mars

- Terraforming Mars

- Life on Mars

- The Moons of Mars

- Martian Meteorites

- Comparative Planetology

- Incidence of Craters

- Counting Craters

- Counting Statistics

- Internal Heat and Geological Activity

- Magnetic Fields of the Terrestrial Planets

- Mountains and Rifts

- Radar Studies of Planetary Surfaces

- Laser Ranging and Altimetry

- Gravity and Atmospheres

- Normal Atmospheric Composition

- The Significance of Oxygen

- Questions

Chapter 7

The Giant Planets and Their Moons

- The Gas Giant Planets

- Atmospheres of the Gas Giant Planets

- Clouds and Weather on Gas Giant Planets

- Internal Structure of the Gas Giant Planets

- Thermal Radiation from Gas Giant Planets

- Life on Gas Giant Planets?

- Why Giant Planets are Giant

- Gas Laws

- Ring Systems of the Giant Planets

- Structure Within Ring Systems

- The Origin of Ring Particles

- The Roche Limit

- Resonance and Harmonics

- Tidal Forces in the Solar System

- Moons of Gas Giant Planets

- Geology of Large Moons

- The Voyager Missions

- Jupiter

- Jupiter's Galilean Moons

- Jupiter's Ganymede

- Jupiter's Europa

- Jupiter's Callisto

- Jupiter's Io

- Volcanoes on Io

- Saturn

- Cassini Mission to Saturn

- Saturn's Titan

- Saturn's Enceladus

- Discovery of Uranus and Neptune

- Uranus

- Uranus' Miranda

- Neptune

- Neptune's Triton

- Pluto

- The Discovery of Pluto

- Pluto as a Dwarf Planet

- Dwarf Planets

- Questions

Chapter 8

Interplanetary Bodies

- Interplanetary Bodies

- Comets

- Early Observations of Comets

- Structure of the Comet Nucleus

- Comet Chemistry

- Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt

- Kuiper Belt

- Comet Orbits

- Life Story of Comets

- The Largest Kuiper Belt Objects

- Meteors and Meteor Showers

- Gravitational Perturbations

- Asteroids

- Surveys for Earth Crossing Asteroids

- Asteroid Shapes

- Composition of Asteroids

- Introduction to Meteorites

- Origin of Meteorites

- Types of Meteorites

- The Tunguska Event

- The Threat from Space

- Probability and Impacts

- Impact on Jupiter

- Interplanetary Opportunity

- Questions

Chapter 9

Planet Formation and Exoplanets

- Formation of the Solar System

- Early History of the Solar System

- Conservation of Angular Momentum

- Angular Momentum in a Collapsing Cloud

- Helmholtz Contraction

- Safronov and Planet Formation

- Collapse of the Solar Nebula

- Why the Solar System Collapsed

- From Planetesimals to Planets

- Accretion and Solar System Bodies

- Differentiation

- Planetary Magnetic Fields

- The Origin of Satellites

- Solar System Debris and Formation

- Gradual Evolution and a Few Catastrophies

- Chaos and Determinism

- Extrasolar Planets

- Discoveries of Exoplanets

- Doppler Detection of Exoplanets

- Transit Detection of Exoplanets

- The Kepler Mission

- Direct Detection of Exoplanets

- Properties of Exoplanets

- Implications of Exoplanet Surveys

- Future Detection of Exoplanets

- Questions

Chapter 10

Detecting Radiation from Space

- Observing the Universe

- Radiation and the Universe

- The Nature of Light

- The Electromagnetic Spectrum

- Properties of Waves

- Waves and Particles

- How Radiation Travels

- Properties of Electromagnetic Radiation

- The Doppler Effect

- Invisible Radiation

- Thermal Spectra

- The Quantum Theory

- The Uncertainty Principle

- Spectral Lines

- Emission Lines and Bands

- Absorption and Emission Spectra

- Kirchoff's Laws

- Astronomical Detection of Radiation

- The Telescope

- Optical Telescopes

- Optical Detectors

- Adaptive Optics

- Image Processing

- Digital Information

- Radio Telescopes

- Telescopes in Space

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Interferometry

- Collecting Area and Resolution

- Frontier Observatories

- Questions

Chapter 11

Our Sun: The Nearest Star

- The Sun

- The Nearest Star

- Properties of the Sun

- Kelvin and the Sun's Age

- The Sun's Composition

- Energy From Atomic Nuclei

- Mass-Energy Conversion

- Examples of Mass-Energy Conversion

- Energy From Nuclear Fission

- Energy From Nuclear Fusion

- Nuclear Reactions in the Sun

- The Sun's Interior

- Energy Flow in the Sun

- Collisions and Opacity

- Solar Neutrinos

- Solar Oscillations

- The Sun's Atmosphere

- Solar Chromosphere and Corona

- Sunspots

- The Solar Cycle

- The Solar Wind

- Effects of the Sun on the Earth

- Cosmic Energy Sources

- Questions

Chapter 12

Properties of Stars

- Stars

- Star Names

- Star Properties

- The Distance to Stars

- Apparent Brightness

- Absolute Brightness

- Measuring Star Distances

- Stellar Parallax

- Spectra of Stars

- Spectral Classification

- Temperature and Spectral Class

- Stellar Composition

- Stellar Motion

- Stellar Luminosity

- The Size of Stars

- Stefan-Boltzmann Law

- Stellar Mass

- Hydrostatic Equilibrium

- Stellar Classification

- The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram

- Volume and Brightness Selected Samples

- Stars of Different Sizes

- Understanding the Main Sequence

- Stellar Structure

- Stellar Evolution

- Questions

Chapter 13

Star Birth and Death

- Star Birth and Death

- Understanding Star Birth and Death

- Cosmic Abundance of Elements

- Star Formation

- Molecular Clouds

- Young Stars

- T Tauri Stars

- Mass Limits for Stars

- Brown Dwarfs

- Young Star Clusters

- Cauldron of the Elements

- Main Sequence Stars

- Nuclear Reactions in Main Sequence Stars

- Main Sequence Lifetimes

- Evolved Stars

- Cycles of Star Life and Death

- The Creation of Heavy Elements

- Red Giants

- Horizontal Branch and Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars

- Variable Stars

- Magnetic Stars

- Stellar Mass Loss

- White Dwarfs

- Supernovae

- Seeing the Death of a Star

- Supernova 1987A

- Neutron Stars and Pulsars

- Special Theory of Relativity

- General Theory of Relativity

- Black Holes

- Properties of Black Holes

- Questions

Chapter 15

Galaxies

- The Milky Way Galaxy

- Mapping the Galaxy Disk

- Spiral Structure in Galaxies

- Mass of the Milky Way

- Dark Matter in the Milky Way

- Galaxy Mass

- The Galactic Center

- Black Hole in the Galactic Center

- Stellar Populations

- Formation of the Milky Way

- Galaxies

- The Shapley-Curtis Debate

- Edwin Hubble

- Distances to Galaxies

- Classifying Galaxies

- Spiral Galaxies

- Elliptical Galaxies

- Lenticular Galaxies

- Dwarf and Irregular Galaxies

- Overview of Galaxy Structures

- The Local Group

- Light Travel Time

- Galaxy Size and Luminosity

- Mass to Light Ratios

- Dark Matter in Galaxies

- Gravity of Many Bodies

- Galaxy Evolution

- Galaxy Interactions

- Galaxy Formation

- Questions

Chapter 16

The Expanding Universe

- Galaxy Redshifts

- The Expanding Universe

- Cosmological Redshifts

- The Hubble Relation

- Relating Redshift and Distance

- Galaxy Distance Indicators

- Size and Age of the Universe

- The Hubble Constant

- Large Scale Structure

- Galaxy Clustering

- Clusters of Galaxies

- Overview of Large Scale Structure

- Dark Matter on the Largest Scales

- The Most Distant Galaxies

- Black Holes in Nearby Galaxies

- Active Galaxies

- Radio Galaxies

- The Discovery of Quasars

- Quasars

- Types of Gravitational Lensing

- Properties of Quasars

- The Quasar Power Source

- Quasars as Probes of the Universe

- Star Formation History of the Universe

- Expansion History of the Universe

- Questions

Chapter 17

Cosmology

- Cosmology

- Early Cosmologies

- Relativity and Cosmology

- The Big Bang Model

- The Cosmological Principle

- Universal Expansion

- Cosmic Nucleosynthesis

- Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

- Discovery of the Microwave Background Radiation

- Measuring Space Curvature

- Cosmic Evolution

- Evolution of Structure

- Mean Cosmic Density

- Critical Density

- Dark Matter and Dark Energy

- Age of the Universe

- Precision Cosmology

- The Future of the Contents of the Universe

- Fate of the Universe

- Alternatives to the Big Bang Model

- Space-Time

- Particles and Radiation

- The Very Early Universe

- Mass and Energy in the Early Universe

- Matter and Antimatter

- The Forces of Nature

- Fine-Tuning in Cosmology

- The Anthropic Principle in Cosmology

- String Theory and Cosmology

- The Multiverse

- The Limits of Knowledge

- Questions

Chapter 18

Life On Earth

- Nature of Life

- Chemistry of Life

- Molecules of Life

- The Origin of Life on Earth

- Origin of Complex Molecules

- Miller-Urey Experiment

- Pre-RNA World

- RNA World

- From Molecules to Cells

- Metabolism

- Anaerobes

- Extremophiles

- Thermophiles

- Psychrophiles

- Xerophiles

- Halophiles

- Barophiles

- Acidophiles

- Alkaliphiles

- Radiation Resistant Biology

- Importance of Water for Life

- Hydrothermal Systems

- Silicon Versus Carbon

- DNA and Heredity

- Life as Digital Information

- Synthetic Biology

- Life in a Computer

- Natural Selection

- Tree Of Life

- Evolution and Intelligence

- Culture and Technology

- The Gaia Hypothesis

- Life and the Cosmic Environment

Chapter 19

Life in the Universe

- Life in the Universe

- Astrobiology

- Life Beyond Earth

- Sites for Life

- Complex Molecules in Space

- Life in the Solar System

- Lowell and Canals on Mars

- Implications of Life on Mars

- Extreme Environments in the Solar System

- Rare Earth Hypothesis

- Are We Alone?

- Unidentified Flying Objects or UFOs

- The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

- The Drake Equation

- The History of SETI

- Recent SETI Projects

- Recognizing a Message

- The Best Way to Communicate

- The Fermi Question

- The Anthropic Principle

- Where Are They?

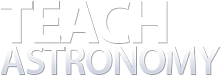

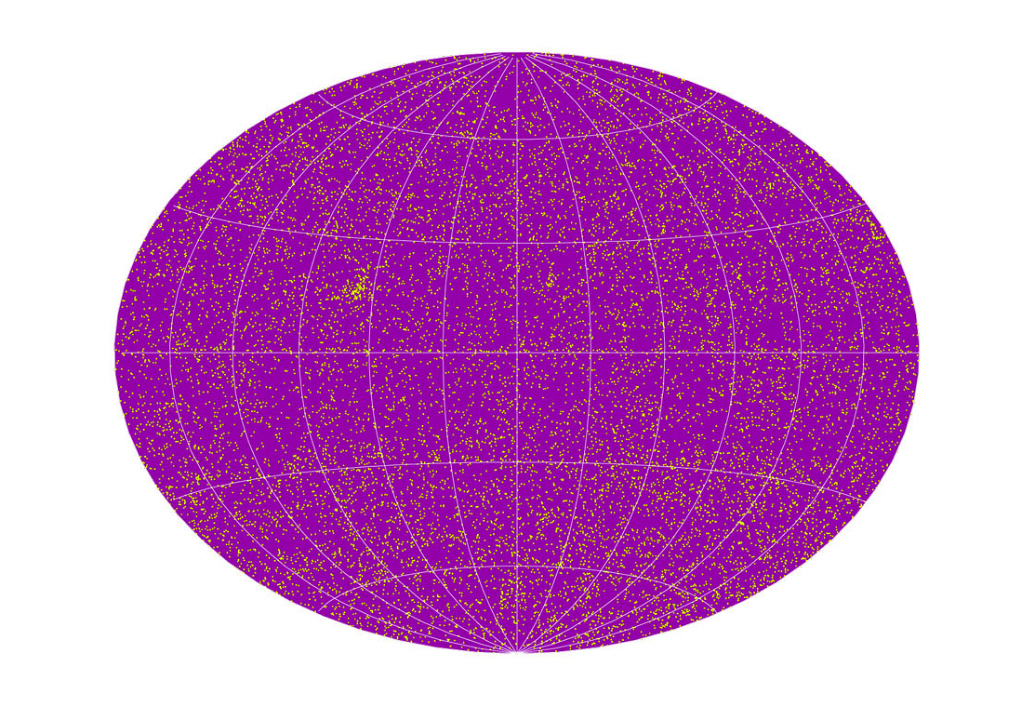

The Distribution of Stars in Space

The night sky blazes with starlight. Go to a site far from any city, and you can see over 6000 stars scattered across the sky. Long before the invention of the telescope, people could plainly see a band of light arching across midnight skies during certain seasons. Myths and legends have been molded around this prominent feature of the night sky. Nearly 2500 years ago, the Greek philosopher Democritus correctly attributed this glow to a mass of unresolved stars, which came to be called the Via Lactea, or Milky Way. The Milky Way was familiar to all prehistoric humans. Sadly, the spread of urban light has made it an unfamiliar sight to most people.

In 1610 Galileo turned his telescope on the Milky Way and confirmed the ancient idea of Democritus that the filmy glow was due to a vast number of unresolved stars. He recognized that if the stars were like the Sun, they must be at vast distances, and the range of star brightnesses within the Milky Way implied a large range of distances. The telescope opened up a sense of the third dimension: depth. We call an entire set of stars that is held together by gravity a galaxy. The Milky Way galaxy contains the Sun and all the other stars in the night sky and has its greatest concentration of stars in one strip of the sky.

How far away are all these stars? Does the distribution of stars have an end? What is the role of the Sun in this great assemblage? These questions get to the heart of an important issue — our place in the larger universe. Astronomers have built up a picture of the Milky Way Galaxy, working up in scale. It starts with a description of the immediate environment of stars, showing that most stars have companions. There is also a thin medium between stars. Astronomers can also identify groups and clusters of stars. All this information is combined to define the architecture of the Milky Way galaxy.

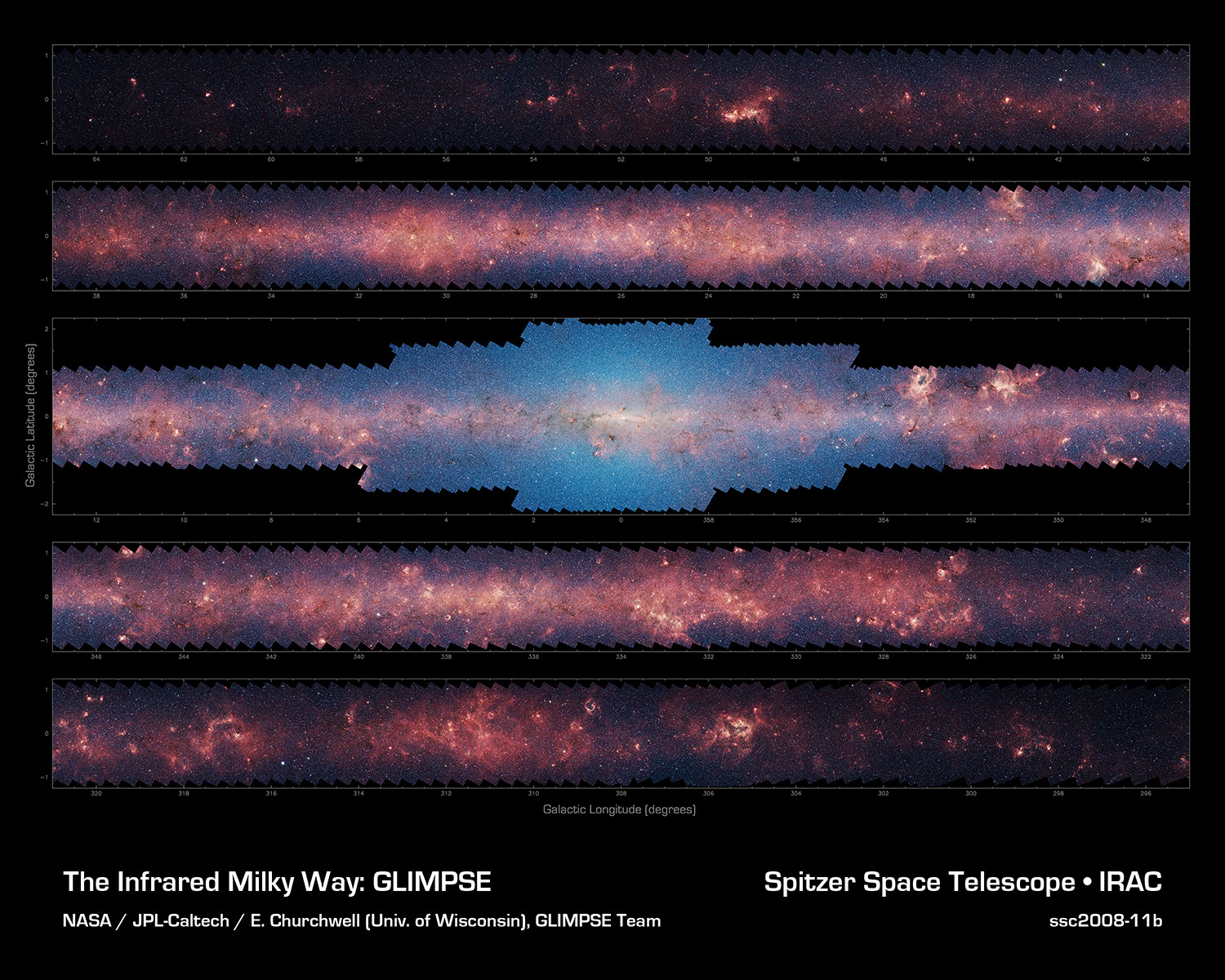

The stars seem to be arrayed above our heads on a two-dimensional backdrop. Measuring the third dimension of distance is a great challenge. Stars differ in absolute brightness by factors of a million or more, so a dwarf star might be 1000 times nearer than a supergiant of the same apparent brightness. Absolute brightness or luminosity is given by L = d2F, where d is distance and F is flux or apparent brightness. Remember that L is the true brightness of an object or the number of photons it emits each second, while F is the brightness we measure on Earth or the number of photons per second we collect with our telescope.

Apparent brightness is a good measure of distance if we can identify stars of the same luminosity. If luminosity is a constant, then F ∝ d-2. This is a statement of the familiar square law inverse. The excellent correlation between F and d means that the flux can be used to calculate distance. But if stars have a larger range in luminosity, apparent brightness is a much poorer indicator of distance. Finally, think of the more realistic situation that an astronomer might face when stars of every type are measured. The range of luminosity on the H-R diagram is so large that any correlation between apparent brightness and distance has been washed out. The appearance of a star gives no useful measure of its distance.

Astronomers can measure distances to some stars directly, using the method of trigonometric parallax. Unfortunately, most of the stars that are visible through a small telescope are too remote for parallax to be measured. However, it turns out that we can learn something about distance simply by observing the way that stars are distributed on the plane of the sky. Go out on a dark night and you will see that some stars appear very close to each other. Are these pairs just caused by the chance alignment of two stars at different distances, or are they connected in some way? As early as 1767, John Michell, who was the father of the idea of black holes, decided that there were too many alignments to be caused by chance. He believed that the stars in each pair were close enough in space to orbit each other by gravity. Michell was an extraordinary thinker, far ahead of his time in many ways. As well as coming up with the concept of black holes, he was the first to understand that earthquakes travel as waves in rock and the first to develop artificial magnets.

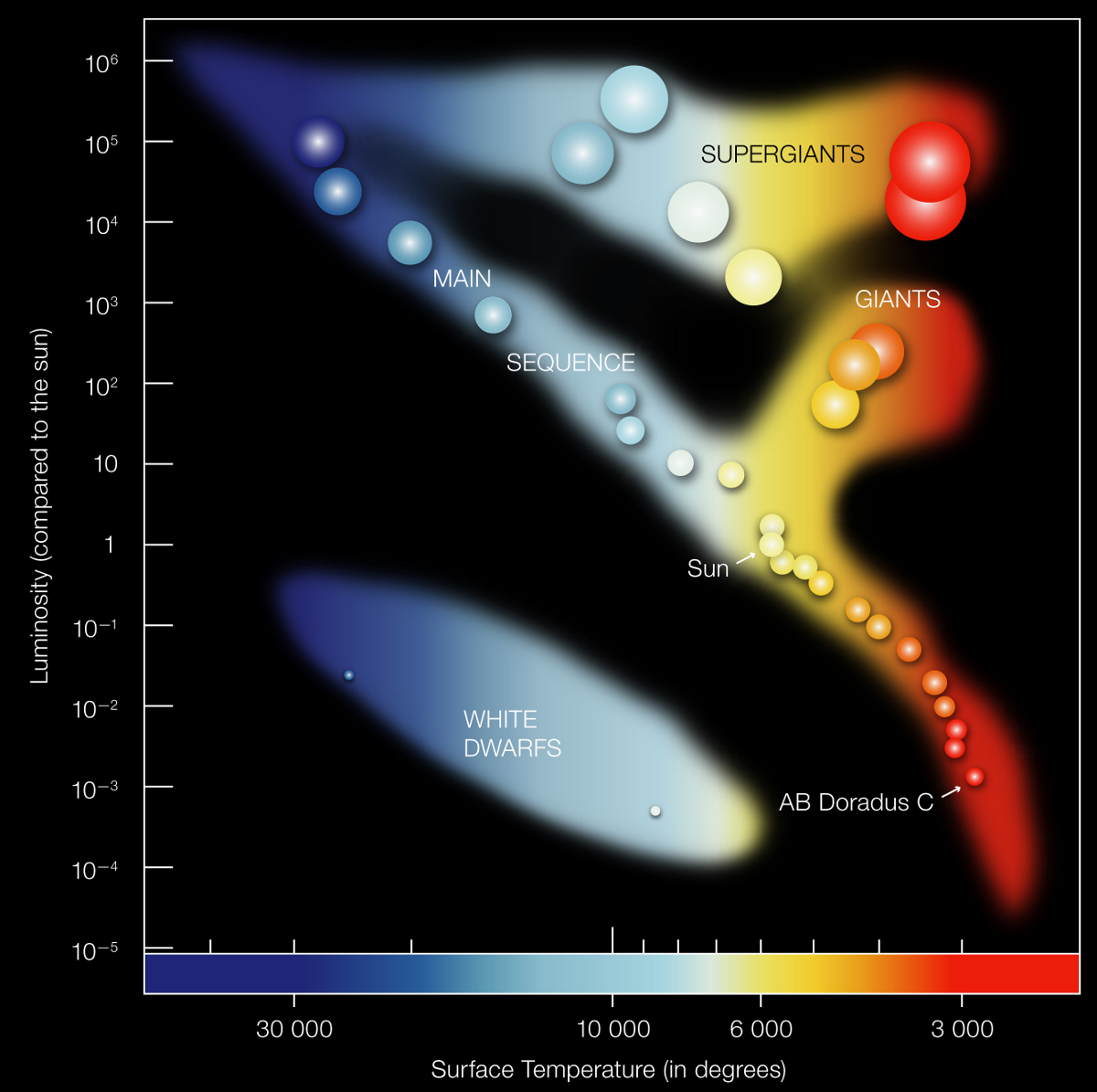

To understand how John Michell deduced that some stars are double, start by understanding two types of distribution: uniform and random. Imagine that stars are distributed in only two dimensions, on a plane. A uniform distribution refers to objects that are separated by equal distances. A uniform distribution of stars would be spread out in a regular grid with equal distances between each one. The distance from any star to its nearest neighbor is always the same. A uniform distribution may be realistic to describe the way atoms are laid out in a crystal, but it is not realistic to describe the way stars are laid out in space.

For a more realistic situation, consider a random distribution. A random distribution refers to objects that are separated by random distances. In this case, the distance between a star and its nearest neighbor star can vary quite widely. However, the average distance between stars is the same as for a uniform distribution. To see that this must be true, remember that the number of stars and the total area are unchanged, so the average spacing is unchanged too. For any particular star, we can ask what the probability is that it will have a neighbor within a certain distance. The average spacing is the distance where the probability is 0.5, so half of the stars will have a nearest neighbor closer than the average spacing and half will have a nearest neighbor farther than the average spacing. The probability of a star having a neighbor within any distance is proportional to the area considered, or the distance squared. In a random distribution, it is certainly possible for stars to be very close to each other, but it does not happen very often.

Stars in the real universe show clustering. A clustered distribution refers to objects that are separated by distances that tend to be smaller than for a random distribution. When stars are clustered on the plane of the sky, the nearest neighbors tend to be separated by small angles. Clustering is revealed by the higher probability of any star having a neighbor at a small separation, compared to a random distribution. Our example uses distributions in two dimensions but the same argument works for a three-dimensional distribution as well. We have described a statistical measure of clustering based on a distribution of nearest neighbor distances. In other words, we cannot claim that a particular pair of stars with small separation is clustered, because small separations will occur by chance in a random distribution as well. However, the statistical approach is very powerful because it allows astronomers to detect departures from a random distribution that are quite subtle. We don't need a statistical test to tell us that a large clump of stars is clustered; it is obvious to the eye.

Here is John Michell's reasoning on double stars. He measured the angles that separated each star in the sky from its nearest neighbor. He then calculated what angles he would measure if the same number of stars were distributed randomly on the sky. He compared the two distributions. Mitchell detected a clear excess of stars with close companions compared with what he would have expected from a random distribution. He concluded that some stars were physically associated — held together in one region of space by gravity. In particular, he identified many pairs of stars, which often differed greatly in apparent brightness, which must be at the same distance. Through his detective work, Michell provided the first clues to how stars are distributed in space.